Overview

When developing RPGs or action games, you inevitably face the challenge of "mass-producing characters." You've created the basic "Slime," but as level design progresses, you need countless variations: "Slime with slightly more HP," "Red Slime with 2x attack power," "Metal Slime that drops specific items."

Many developers first try simply copying and pasting the base scene (e.g., Slime.tscn) and manually adjusting parameters one by one. However, this approach quickly falls apart. If you later want to "slightly increase movement speed for all slimes," you'd have to open and modify every copied scene.

This article explains two Godot features that elegantly solve this problem: Scene Inheritance and Editable Children.

Method 1: Scene Inheritance - The Recommended Standard

Scene inheritance brings the concept of "class inheritance" from object-oriented programming to Godot's scene system. You can create new "child" scenes that inherit all the structure and functionality of an existing "parent" scene. When prioritizing reusability and maintainability, this is the first choice.

How Scene Inheritance Works and Its Benefits

-

Manage Only Differences: In child scenes, you can freely change properties inherited from the parent scene (node positions, script

@exportvariables, etc.). Changed properties show a yellow "reset" icon in the inspector, making differences from the parent immediately visible. -

Parent Changes Auto-Propagate to Children: This is the most powerful benefit. When you change the parent scene's (

BaseEnemy.tscn) structure or add new script features, those changes automatically propagate to all child scenes. This lets you balance "bug fixes common to all characters" with "individual adjustments for specific characters."

Practical Code Example: Creating Variations Through Inheritance

Let's see concrete code.

1. Create the Base Enemy Scene (BaseEnemy.tscn)

First, create BaseEnemy.tscn as the base for all enemies and attach a script like this:

# BaseEnemy.gd

extends CharacterBody2D

@export var health: int = 100

@export var attack_power: int = 10

@export var speed: float = 50.0

func _physics_process(delta: float) -> void:

# Simple movement logic (omitted here)

pass

func take_damage(amount: int) -> void:

health -= amount

print("%s took %d damage, %d HP left." % [self.name, amount, health])

if health <= 0:

die()

func die() -> void:

print("%s has been defeated!" % self.name)

queue_free()

2. Create an Inherited Scene (StrongEnemy.tscn)

Right-click BaseEnemy.tscn in the file system dock and select "New Inherited Scene," saving it as StrongEnemy.tscn. At this point, it looks and functions exactly like BaseEnemy.

3. Override Properties and Extend Functionality in the Inherited Scene

Open StrongEnemy.tscn and check the inspector. The health and attack_power exported with @export in BaseEnemy.gd are displayed. Change these values directly:

Health: 250Attack Power: 25

You can also attach a unique script to StrongEnemy to extend parent functionality:

# StrongEnemy.gd

extends "res://BaseEnemy.gd"

# Override parent's die() function to add special processing

func die() -> void:

print("A strong enemy lets out a final roar!")

# Call super.die() to execute parent's die() function (queue_free(), etc.)

super.die()

Note: When

queue_free()is called, the node is removed from the tree on the next frame. Holding references to deleted nodes can cause null reference errors. When signals are connected or references exist from other nodes, make it a habit to handleNOTIFICATION_PREDELETEbefore deletion or check validity withis_instance_valid().

Method 2: Editable Children - Ad-hoc Customization for Limited Cases

Editable Children lets you directly edit the internal nodes of another scene (child scene) instanced in a scene, on the spot. It's convenient since you don't need to create new scene files, but changes are one-time only with no reusability.

Use Cases

This feature shines when you want to make "just this one entity, placed in this specific spot, in this scene" special.

- Increase only one golem's arm

CollisionShape2Din a specific boss room to widen attack range. - Set

speedto 0 in the script for just the first enemy appearing in the tutorial so it doesn't move.

It's very convenient for such "one-time" adjustments.

Steps

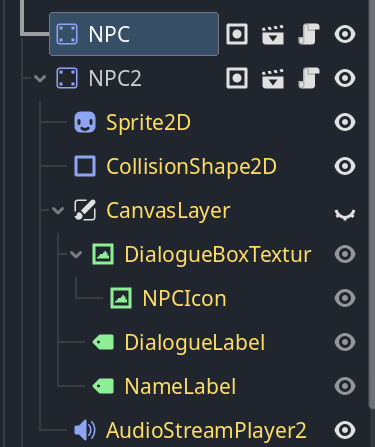

- Place

BaseEnemy.tscnas an instance in the main scene. - Right-click the instanced

BaseEnemynode in the scene tree and check "Editable Children." - The

BaseEnemyhierarchy expands in the scene tree, allowing you to directly select internalSprite2DorCollisionShape2Dand change properties in the inspector.

Common Mistakes and Best Practices

Follow these guidelines to use both features effectively:

| Common Mistake | Best Practice |

|---|---|

| Using Editable Children for everything | Always consider scene inheritance if there's any possibility of reuse. If you think "I might use this again later," don't hesitate to create an inherited scene. |

| Making inheritance hierarchy too deep | Keep inheritance to 2-3 levels as a rule. For more complexity, consider components (adding functionality as child nodes) or data-driven design with Resource instead of inheritance. Signs like "child behavior becomes unpredictable when changing parent" or "can't track what's defined at which level" indicate it's time to reconsider design. |

| Assuming child state in parent scenes | Design parent scenes to be self-contained without depending on children. Parents provide generic functionality; children determine specific behavior. |

| Overusing scripts for property changes | Actively use @export variables for parameters like HP, attack power, speed. This allows designers to safely adjust from the inspector without being programmers. |

Advanced Topics: Performance and Alternative Patterns

Performance Impact

Fundamentally, neither scene inheritance nor Editable Children has significant direct impact on runtime performance. Both methods are ultimately interpreted by the engine as a single scene tree.

Alternative Pattern: Data-Driven Design with Resources

For larger, more complex games (e.g., RPGs with hundreds of monster types), managing with scene inheritance alone can become cumbersome. In such cases, data-driven design using Resource objects to separate character parameters as data is effective.

- Create a script called

CharacterData.gdthat extendsResource, defining variables like HP and attack power with@export. - Right-click in the inspector and create multiple

CharacterDataresources from "New Resource" (e.g.,slime_data.tres,goblin_data.tres). - Add an

@export var character_data: CharacterDatavariable to theBaseEnemyscene's script. - In the

_ready()function, read HP and attack power values from thecharacter_dataresource and set them to your own properties.

With this method, even as enemy types increase, only one scene file (BaseEnemy.tscn) is needed, and parameter adjustments are done in resource files (.tres).

Summary and Next Steps

We've explained two main approaches for creating character variations:

- Scene Inheritance: The standard for creating reusable, maintainable templates. Should be adopted as a basic project strategy.

- Editable Children: A convenient exception for fine-tuning just one instance placed in a specific scene.

Mastering these concepts will make your Godot projects more organized and scalable.

What to Learn Next

- Data-Driven Design with Resources: Learn the alternative pattern introduced here more deeply for more flexible designs.

- Composition Over Inheritance: A principle of object-oriented design. In Godot, designing by "composing" functionality by adding nodes as children is very powerful.